Casady & Greene

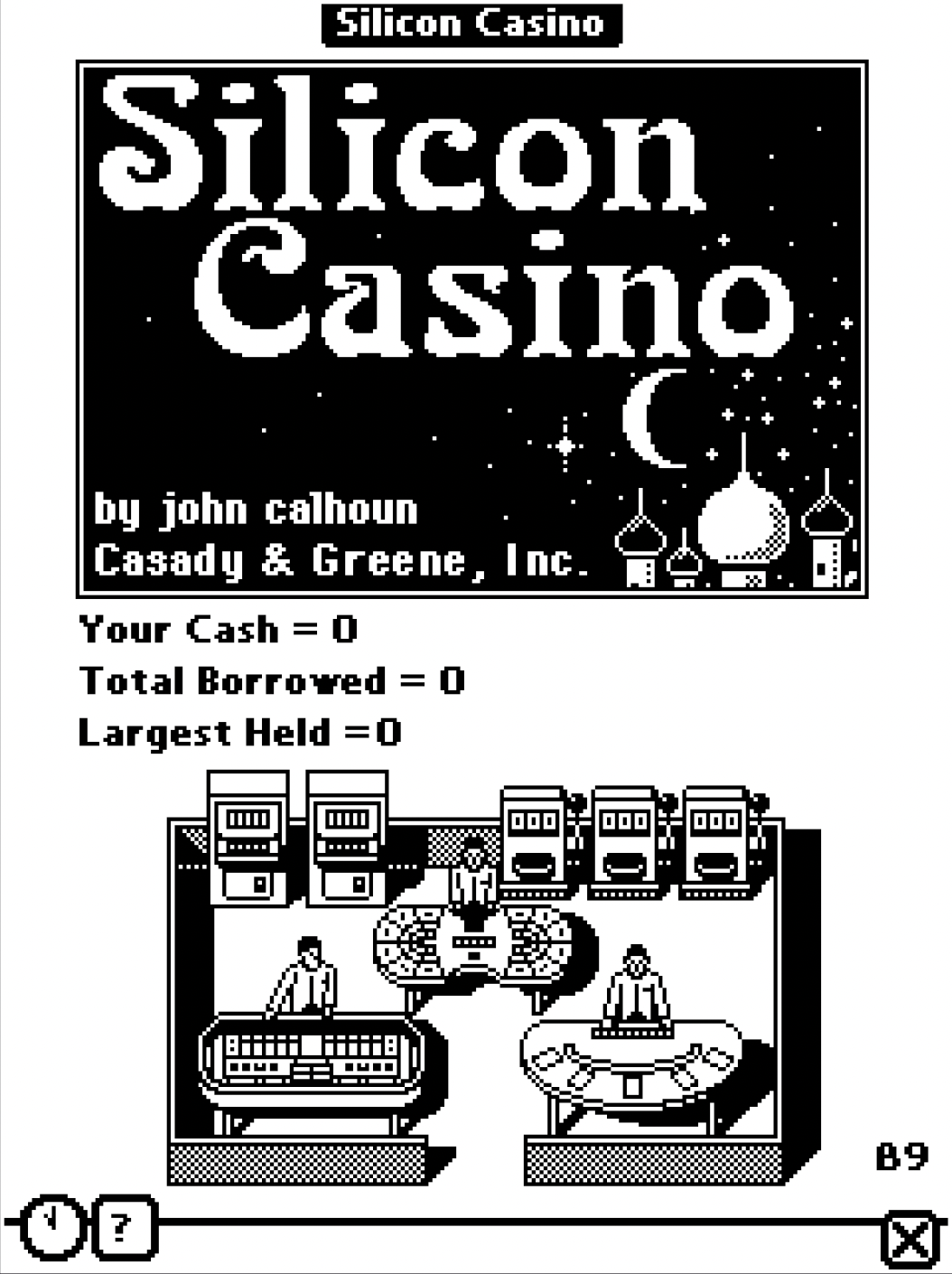

So I recently put together a disk image containing the sources and tools that I used to create the computer games that I wrote for Casady & Greene, Inc. (C&G) back in the 1990’s. Some recovery was required to obtain these files. I’m pleased with the result though. If you can get one of the early-Macintosh emulators up and running such as Basilisk II, Sheepshaver or MiniVMac you should be able to download, unzip and mount the disk image. Everything should then be there to allow you to compile, link and build these old commercial games — 1990’s style.

Shareware

I have to begin by mentioning Steven Levy’s book, Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution — which I must have read around 1990 or so. Don’t be mislead by the title, it is not about black hats trying to pwn military data centers. Instead the book is broken into sections that each cover a specific point in the history of the computer when individuals got their hands on these new machines and pressed them into service to perform sometimes new and wonderful tasks. Levy lays out a number of milestones of the birth of computer culture (or more specifically “Hacker culture”).

I was most fascinated by the section in the book that talked about Sierra On-Line, Inc. and the early Apple II gaming authors that came along with Ken and Roberta Williams to play D&D, code and eat pizza to all hours of the night. I saw a kinship with the game authors — my having also fallen into a pattern of coding to all hours of the night. But I wasn’t being published and, if you read my previous post, you know I was also barely paying for the occasional pizza.

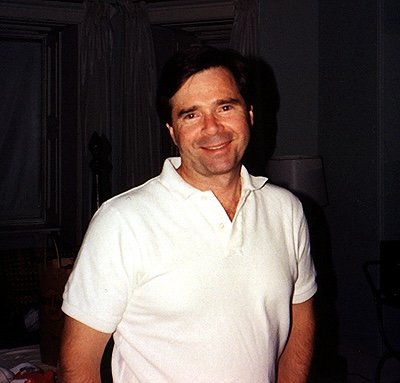

On a lark then, I reached out to a couple of software publishers to see if they might be interested in publishing a game that I had written. Casady & Greene, Inc. responded, “What do you got?” Glider was out there as shareware — rather than trying to “sell” them on the game I just suggested that they locate it, pull it down, and try the game for themselves. Soon we were agreeing to a color re-write of Glider with a bigger “house” (more levels).

Casady & Greene, Inc.

In some ways, Casady & Greene, Inc. (C&G) were not unlike Sierra On-Line. Besides both being geographically west of the Sierra mountains in northern California, they were also small, family-run companies headed by entrepreneurial types. Though the 1980’s were coming to a close, California still seemed like this rarified place at that time — perhaps the only place — where these kinds of businesses blossomed. There was a tech savviness in abundance there of course but I’m not sure though why there seemed to be such a strong entrepreneurial spirit as well.

Michael Greene came across as a programmer first, businessman second. This is true at least in my relationship with him. I remember when he asked me to sign a business contract that I began to panic a bit because the document was legally binding and not something I had any familiarity with at all. I remember being suspicious about a clause referring to “the right to first refusal”. Casady & Greene wanted this ability — the ability to publish, if they so desired, any program I wrote from then on out. I mean, from my point of view we were signing a contract for the publication of Glider — what was this “right to everything I ever write” crap?

Very matter of factly though Michael responded that from the company’s perspective they were investing not in the game Glider but in me as the author. Glider they hoped would be the first fruit born of that relationship but that a company is also looking out for possible future titles, future business. It was from that kind of honesty that I quickly came to trust Michael.

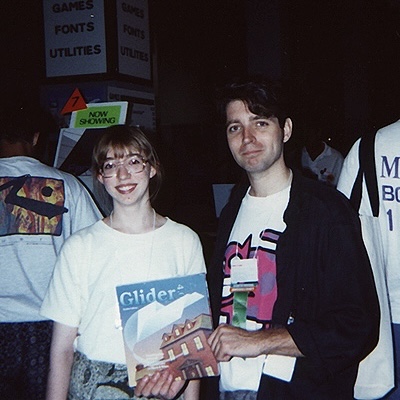

I’m not sure many people are interested in hearing about C&G inviting me out to my first MacWorld Expo in Boston or their flying me out to California where I saw their offices in the strip-mall in Salinas and got to meet the entire C&G family. Or those days when I sent beta versions of my games to their office via modem.

An Era

With the distance of some thirty or so years now I see that era for what it was — an “era”. A small window of opportunity for small entrepreneurs like Michael Greene and Robin Casady to start up a publishing house in a small-town strip mall — young employees creating manuals on word processors, stuffing floppies into boxes to be shipped out. A sales team worked with distributors and advertising ... the whole crew flying out to trade shows (and to also sell product on the showroom floor to somewhat defray the cost of the outing).

And maybe from my description above you can get a sense that the whole period of my life in the early 90’s when I was up late writing games for C&G, popping out twice a year to an expo, was a kind of an “era” for me as well. The experiences were new and exciting as I think the times were as well. The Macintosh was the underdog when the PC entered the scene but it was a machine that had somehow captivated a number of us. In a sense maybe we were all, that is all Macintosh devotees, part of a larger family. (The Mac expos being a kind of family reunion if I were to beat this metaphor to death.)

Something happened in this period of my life that has stuck with me all these years.

This Could Be You

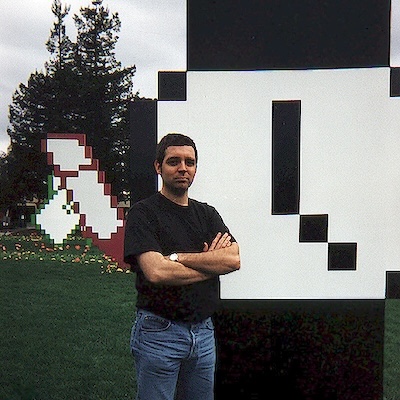

C&G were somehow tapped by Apple Computer and invited to send an engineer of theirs to a “kitchen” Apple was hosting. The kitchen was an event at Apple headquarters where Apple engineers would be tasked to help outside programmers learn to develop for some kind of Apple technology. Don’t laugh when I tell you it was for the just-about-to-be-released Newton hand held computer. C&G gave me a holler and, yes, I flew out to California to spend a week at Apple HQ learning how to write for the Newton.

You have to keep in mind that I was a non-CS (non Computer Science) major from Kansas who wrote games sitting in a conference room with actual Apple engineering, using Apple hardware to bring up an app on a futuristic device not yet shipping. I did my best, sussed out the limited gaming options for the thing, but managed to get a small coin you could drag around the screen with a stylus by the time the kitchen wrapped up.

But the thing I want to tell you about is the little meet and greet that Apple had on one of the last days of the whole Newton dev confab. Somehow I found myself talking to a young Apple engineer that looked about my age. He was Hispanic (I’m about one-quarter Hispanic) and had a little sample app he had written he called Mr. Avisador that was something like a Magic-8 ball, giving you random advice to the yes/no questions you entered.

Hanging out at a beer-bash-like event I must have expressed my jealousy that he was working “At Apple!”. But he came back with, “You could work here.” I was incredulous, “Me? I don’t have a CS degree — didn’t go to Carnegie Mellon....” “There are a lot of engineers here that don’t have CS degrees. You wrote a bunch of apps and shipped them, right? Most of the programmers here have never shipped anything before starting.”

It was a jarring thought for my lowered self-esteem to consider. And so, maybe like my surprise at having been able to go from shareware to published game author, I found myself some years later beginning what would become a twenty-six career at Apple.

I started at Apple in October, 1995 — more or less just as the company began to circle the drain and the layoffs were about to begin. If Apple had indeed folded back then I would have turned out the light and left the field of programming. I really never was a programmer, I was a Macintosh programmer.

In Closing

Michael, for personal reasons, was eventually to leave the company but Casady & Greene continued on. The “industry” was changing in small and subtle ways that would over time shutter the ma and pa software houses as they had existed.

In the end, as far as assets go, an engineer named Jeff Robbin from the Chicago area was probably C&G’s best. His Conflict Catcher, a Macintosh utility, was no doubt C&G’s best seller. Unless of course that would be the MP3 application called SoundJam that Jeff Robbin also wrote for C&G. You may have heard of SoundJam, if not you will have heard of it when it was purchased from C&G by Apple and re-branded Apple’s iTunes.

Likely it was the sale of the century for C&G. And maybe they too saw the writing on the wall at last since shortly after they closed up shop. An era had indeed closed.

Postscript

I should mention that C&G’s closing down meant the rights to the games that I had written for them reverted back to me. And to circle back to the top of this post, that is how I am able to put all the sources to those games out there.